Varieties of Arabic

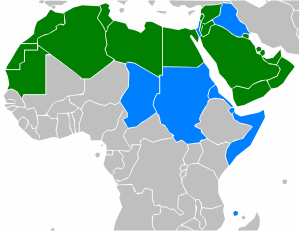

The Arabic language is a Semitic language with many varieties that diverge widely from one another—both from country to country and within a single country. A distinction is to be made between Classical/Standard Arabic (often called Modern Standard Arabic or MSA) and these "colloquial" variants. In sociolinguistic terms, Arabic in its native environment typically occurs in a "diglossic" situation, meaning that native speakers learn and use two substantially different language forms in different aspects of their lives. In the case of Arabic, the regionally prevalent variety is learned as a speaker's native language and is used for nearly all everyday speaking situations throughout life, also including some films and plays, and (rarely) in some literature. These varieties (or dialects) are called العامية (al-)`āmmiyya (East) or الدارجة (ad-)dārija (West) in Arabic.

A second, quite different variety, Modern Standard Arabic (الفصحى (al-)fuṣḥā in Arabic for both CA and MSA), is learned in school and is used for most printed material, public media, and other formal situations. The extent to which the local vernacular varieties of Arabic utilize the literary (or "classical") versions used in formal situations varies from country to country, speaker to speaker (education, exposure and personal preferences), and depends on the topic and situation.

Colloquial and formal Arabic certainly do overlap; as a matter of fact it is very difficult to find a situation where one type is used exclusively. For example, MSA is used in formal speeches or interviews. However, just as soon as the speaker diverts away from his well-prepared speech in order to add a comment or respond to a question, the rate of colloquial usage in this speech increases dramatically. How much MSA versus colloquial is used depends on the speaker, the topic, and the situation - amongst other factors. At the other end of the spectrum, public education, as well as exposure to mass media, has introduced MSA elements amongst the least educated so it would be equally difficult to find an Arab speaker whose speech is totally unaffected by MSA.[1]

Contents |

History

Descended from Old North Arabian dialects of pre-Islamic Arabia, early Arabic had noticeable dialect distinctions—in particular between Qahtanite, Adnan, and Himyar. With the spread of Islam in the 7th century, Qur'anic Arabic became the most prevalent dialect.

Vernacular Arabic was first recognized as a written language in contrast to Classical Arabic the 17th century Ottoman Egypt, as the Cairo elite formed a trend towards colloquial writing. A record of the Cairo vernacular of the time is found in the dictionary compiled by Yusuf al-Maghribi.

In modern times, the spoken dialects of people throughout the Arab world differ notably from the Literary Arabic and from each other.

General varieties

The main division between varieties of spoken Arabic is between the Maghrebi (North African) varieties (characterized by a first person singular in n- and use of /ʃ/ at the end of a verb for negation) and those of the Middle East, followed by that between sedentary varieties and the much more conservative Bedouin varieties. "Peripheral" varieties located in countries where Arabic is not a dominant language (e.g., Turkey, Iran, Cyprus, Chad, and Nigeria) are particularly divergent in some respects, especially vocabulary, being less influenced by classical Arabic. However, historically they fall within the same dialect classifications as better-known varieties. In some areas, different religious communities speak slightly different varieties. In Baghdad Christians and Jews speak a qeltu-variety while the Muslims speak a gilit-variety. (Both words mean "I said". For further discussion, see Judeo-Arabic languages.)

The Maltese language is a Semitic language descended from Siculo-Arabic whose vocabulary has acquired a large number of loanwords from Sicilian and Standard Italian. Due to these influences, Maltese has occasionally been referred to as a "mixed language"[2]. Maltese in its standard form also uses a Latin-based alphabet and is the only Semitic official language within the European Union.

Probably the most divergent of non-creole Arabic varieties is Cypriot Maronite Arabic, a nearly extinct variety heavily influenced by Greek.

Some of these varieties are mutually unintelligible from other forms of Arabic. Middle Eastern and North African varieties (excluding those spoken in Egypt which are closer to the Middle Eastern forms) are particularly disparate with the speakers of the latter only being capable of comprehending the former due to the popularity of Egyptian films and other media.

One factor in the differentiation of the varieties is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided a significant number of new words, and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order; however, a much more significant factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine, Egyptian and Libyan fiih, and Moroccan and Algerian kayen all mean "there is", and come from Arabic yakuun, fiihi, kaa'in respectively.

The spoken varieties of Arabic have occasionally been written, usually in the Arabic alphabet. Notably, many plays and poems, as well as a few other works (even translations of Plato) exist in Lebanese Arabic and Egyptian Arabic; books of poetry, at least, exist for most varieties. In Algeria, colloquial Maghrebi Arabic was taught as a separate subject under French colonization, and some textbooks exist. Mizrahi Jews throughout the Arab world who spoke Judeo-Arabic dialects rendered newspapers, letters, accounts, stories, and translations of some parts of their liturgy in the Hebrew alphabet, adding diacritics and other conventions for letters that exist in Judeo-Arabic but not Hebrew. The Latin alphabet was advocated for Lebanese Arabic by Said Aql, whose supporters published several books in his transcription. Later, in 1994, Abdelaziz Pasha Fahmi, a member of the Academy of the Arabic Language in Egypt proposed the replacement of the Arabic alphabet with the Latin alphabet. His proposal was discussed in two sessions in the communion but was rejected, and was faced with strong opposition in cultural circles.

Arabic-based pidgins, with a small, largely Arabic vocabulary that lacks most Arabic morphological features, have been widespread along the southern edge of the Sahara through the present day; the medieval geographer al-Bakri records a text in one (in a place probably corresponding to modern Mauritania) in the 11th century. In some areas, especially around the southern Sudan, these have creolized; see the list below.

Classification

Pre-Islamic varieties

- Ancient North Arabian

- Safaitic

- Lihyanitic

- Thamudic

- Hasaitic

- Ancient South Arabian

- Sabaean

- Minaean

- Qatabanian

- Hadramautic

- Nabataean language

- Classical Arabic

Islamic Golden Age

- Classical Arabic

Pre-Modern varieties

Western varieties

- Maghrebi Arabic

- Koines

- Moroccan Arabic (ISO 639-3:ary)

- Algerian Arabic (ISO 639-3:arq)

- Tunisian Arabic (ISO 639-3:aeb)

- Libyan Arabic (ISO 639-3:ayl)

- Fully pre-Hilalian

- Jebli Arabic

- Jijel Arabic

- Siculo-Arabic (extinct)

- Maltese language (ISO 639-3:mlt)

- Bedouin

- Saharan Arabic (ISO 639-3:aao)

- Hassaniya Arabic (ISO 639-3:mey)

- Koines

- Andalusian Arabic (extinct)

Central varieties

- Egyptian Arabic (ISO 639-3:arz)

- Sa'idi Arabic (ISO 639-3:aec)

- Sudanese Arabic (ISO 639-3:apd)

Northern varieties

- North Mesopotamian Arabic (ISO 639-3:ayp)

- Levantine Arabic (Eastern Arabic)

- North Levantine Arabic

- North Syrian Arabic

- Lebanese/Central Syrian dialects (ISO 639-3:apc (North Levantine Arabic))

- Lebanese Arabic

- Syrian Arabic

- Palestinian Arabic (South Levantine Arabic) (ISO 639-3:ajp)

- Bedawi Arabic (ISO 639-3:avl)

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic (ISO 639-3:acy)

- North Levantine Arabic

- Iraqi Arabic (ISO 639-3, Mesopotamian acm)

- qeltu-varieties

- Baghdad Arabic (Jewish)

- gilit-varieties

- Baghdad Arabic

- qeltu-varieties

Southern varieties

- Gulf Arabic (ISO 639-3:afb)

- Bahrani Arabic (ISO 639-3:abv)

- Najdi Arabic (ISO 639-3:ars)

- Hijazi Arabic (ISO 639-3:acw)

- Yemeni Arabic

- Dhofari Arabic (ISO 639-3:adf)

- Omani Arabic (ISO 639-3:acx)

- Shihhi Arabic (ISO 639-3:ssh)

Peripheries

- Central Asian Arabic

- Khuzestani Arabic

- Shirvani Arabic (extinct)

- Chadian Arabic (Baggara, Shuwa Arabic) (ISO 639-3:shu)

- Nigerian Arabic

Sectarian varieties

- Judeo-Arabic (ISO 639-3:jrb)

Creoles

- Nubi Creole Arabic

- Babalia Creole Arabic

- Sudanese Creole Arabic (Juba Arabic)

Country-based dialects

- Algerian Arabic

- Bahraini Arabic

- Chadian Arabic

- Egyptian Arabic

- Emirati Arabic

- Iraqi Arabic

- Jordanian Arabic

- Kuwaiti Arabic

- Lebanese Arabic

- Libyan Arabic

- Hassaniya Arabic (Mauritanian Arabic)

- Moroccan Arabic

- Nigerian Arabic

- Omani Arabic

- Palestinian Arabic

- Qatari Arabic

- Sahrawi Arabic

- Saudi Arabic

- Sudanese Arabic

- Syrian Arabic

- Tunisian Arabic

- Yemeni Arabic

Diglossic variety

- Modern Standard Arabic (ISO 639-3:arb)

Sedentary vs. Bedouin

A basic dialectal distinction that cuts across the entire geography of the Arabic-speaking world is between sedentary and Bedouin varieties. Across the Levant and North Africa (i.e. the areas of post-Islamic settlement), this is mostly reflected as an urban (sedentary) vs. rural (Bedouin) split, but the situation is more complicated in Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. The distinction stems from the settlement patterns in the wake of the Arab conquests. As regions were conquered, army camps were set up that eventually grew into cities, and settlement of the rural areas by Bedouins gradually followed thereafter. In some areas, sedentary dialects are divided further into urban and rural variants.

The most obvious phonetic difference between the two dialect groups is the pronunciation of the letter ق qaaf, which is voiced in the Bedouin dialects (usually /ɡ/, but sometimes a palatalized variation /d͡ʒ/ or /ʒ/), but voiceless in the sedentary dialects (/q/ or /ʔ/) (the former realisation being mostly associated with the countryside, the latter being considered typically urban). The other major phonetic difference is that the Bedouin dialects preserve the Classical Arabic (CA) interdentals /θ/ ث and /ð/ ذ, and merge the CA emphatic sounds /dˤ/ ض and /ðˤ/ ظ into /ðˤ/ rather than sedentary /dˤ/.

The most significant differences are in syntax. The sedentary dialects in particular share a number of common innovations from CA. This has led to the suggestion, first articulated by Charles Ferguson, that a simplified koiné language developed in the army staging camps in Iraq, from whence the remaining parts of the modern Arab world were conquered.

In general the Bedouin dialects are more conservative than the sedentary dialects and the Bedouin dialects within the Arabian peninsula are even more conservative than those elsewhere. Within the sedentary dialects, the western varieties (particularly, Moroccan Arabic) are less conservative than the eastern varieties.

Variation

Morphology and syntax

- In the imperfect, Maghrebi Arabic has replaced first person singular /ʔ-/ with /n-/, and the first person plural, originally marked by /n-/ alone, is also marked by the /-u/ suffix of the other plural forms.

- Moroccan Arabic has greatly rearranged the system of verbal derivation, so that the traditional system of forms I through X is not applicable without some stretching. It would be more accurate to describe its verbal system as consisting of two major types, triliteral and quadriliteral, each with a mediopassive variant marked by a prefixal /t-/ or /tt-/.

- The triliteral type encompasses traditional form I verbs (strong: /ktb/ "write"; geminate: /ʃəmm/ "smell"; hollow: /biʕ/ "sell", /ɡul/ "say", /xaf/ "fear"; weak /ʃri/ "buy", /ħbu/ "crawl", /bda/ "begin"; irregular: /kul/-/kla/ "eat", /ddi/ "take away", /ʒi/ "come").

- The quadriliteral type encompasses strong [CA form II, quadriliteral form I]: /sˤrˤfəq/ "slap", /hrrəs/ "break", /hrnən/ "speak nasally"; hollow-2 [CA form III, non-CA]: /ʕajən/ "wait", /ɡufəl/ "inflate", /mixəl/ "eat" (slang); hollow-3 [CA form VIII, IX]: /xtˤarˤ/ "choose", /ħmarˤ/ "redden"; weak [CA form II weak, quadriliteral form I weak]: /wrri/ "show", /sˤqsˤi/ "inquire"; hollow-2-weak [CA form III weak, non-CA weak]: /sali/ "end", /ruli/ "roll", /tiri/ "shoot"; irregular: /sˤifətˤ/-/sˤafətˤ/ "send".

- There are also a certain number of quinquiliteral or longer verbs, of various sorts, e.g. weak: /pidˤali/ "pedal", /blˤani/ "scheme, plan", /fanti/ "dodge, fake"; remnant CA form X: /stəʕməl/ "use", /stahəl/ "deserve"; diminutive: /t-birˤʒəz/ "act bourgeois", /t-biznəs/ "deal in drugs".

- Note that those types corresponding to CA forms VIII and X are rare and completely unproductive, while some of the non-CA types are productive. At one point, form IX significantly increased its productivity over CA, and there are perhaps 50-100 of these verbs currently, mostly stative but not necessarily referring to colors or bodily defects. However, this type is no longer very productive.

- Due to the merging of short /a/ and /i/, most of these types show no stem difference between perfect and imperfect, which is probably why the languages has incorporated new types so easily.

- Egyptian Arabic, probably under the influence of Coptic, puts the demonstrative pronoun after the noun (/al-X da/ "this X" instead of CA /haːðaː l-X/) and leaves interrogative pronouns in situ rather than fronting them, as in other dialects.

All varieties, sedentary and Bedouin, differ in the following ways from Classical Arabic (CA):

- The order subject-verb-object may be more common than verb-subject-object.

- Verbal agreement between subject and object is always complete.

- In CA, there was no number agreement between subject and verb when the subject was third-person and the subject followed the verb.

- Loss of case distinctions. (ʼIʻrāb)

- Loss of original mood distinctions other than the indicative and imperative (i.e. subjunctive, jussive, energetic I, energetic II).

- The dialects differ in how exactly the new indicative was developed from the old forms. The sedentary dialects adopted the old subjunctive forms (feminine /iː/, masculine plural /uː/), while many of the Bedouin dialects adopted the old indicative forms (feminine /iːna/, masculine plural /uːna/).

- The sedentary dialects developed new mood distinctions; see below.

- Loss of dual marking everywhere except on nouns.

- A frozen dual persists as the regular plural marking of a small number of words that normally come in pairs (e.g. eyes, hands, parents).

- In addition, a productive dual marking on nouns exists in most dialects. (Tunisian and Moroccan Arabic are exceptions.) This dual marking differs syntactically from the frozen dual in that it cannot take possessive suffixes. In addition, it differs morphologically from the frozen dual in various dialects, such as Levantine Arabic.

- The productive dual differs from CA in that its use is optional, whereas the use of the CA dual was mandatory even in cases of implicitly dual reference.

- The CA dual was marked not only on nouns by also on verbs, adjectives, pronouns and demonstratives.

- Development of an analytic genitive construction to rival the constructed genitive.

- Compare the similar development of shel in Modern Hebrew.

- The Bedouin dialects make the least use of the analytic genitive. Moroccan Arabic makes the most use of it, to the extent that the constructed genitive is no longer productive, and used only in certain relatively frozen constructions.

- The relative pronoun is no longer inflected. (In CA, it took gender, number and case endings.)

- Pronominal clitics ending in a short vowel moved the vowel before the consonant.

- Hence, second singular /-ak/ and /-ik/ rather than /-ka/ and /-ki/; third singular masculine /-uh/ rather than /-hu/.

- Similarly, the feminine plural verbal marker /-na/ became /-an/.

- Because of the absolute prohibition in all Arabic dialects against having two vowels in hiatus, the above changes occurred only when a consonant preceded the ending. When a vowel preceded, the forms either remained as-is or lost the final vowel, becoming /-k/, /-ki/, /-h/ and /-n/, respectively. Combined with other phonetic changes, this resulted in multiple forms for each clitic (up to three), depending on the phonetic environment.

- The verbal markers /-tu/ (first singular) and /-ta/ (second singular masculine) both became /-t/, while second singular feminine /-ti/ remained.

- In the dialect of southern Nejd (including Riyadh), the second singular masculine /-ta/ has been retained, but takes the form of a long vowel rather than a short one as in Classical Arabic.

- The forms given here were the original forms, and have often suffered various changes in the modern dialects.

- All of these changes were triggered by the loss of final short vowels (see below).

- Various simplifications have occurred in the range of variation in verbal paradigms.

- Third-weak verbs with radical /w/ and radical /j/ (traditionally transliterated y) have merged in the form I perfect tense. (They had already merged in CA, except in form I.)

- Form I perfect faʕula verbs have disappeared, often merging with faʕila.

- Doubled verbs now have the same endings as third-weak verbs.

- Some endings of third-weak verbs have been replaced by those of the strong verbs (or vice-versa, in some dialects).

All dialects except some Bedouin dialects of the Arabian peninsula share the following innovations from CA:

- Loss of the inflected passive (i.e., marked through internal vowel change) in finite verb forms.

- New passives have often been developed by co-opting the original reflexive formations in CA, particularly verb forms V, VI and VII. (In CA these were derivational, not inflectional, as neither their existence nor exact meaning could be depended upon; however, they have often been incorporated into the inflectional system, especially in more innovative sedentary dialects.)

- Hassaniya Arabic contains a newly developed inflected passive that looks somewhat like the old CA passive.

- Najdi Arabic has retained the inflected passive up to the modern era, though this feature is on its way to extinction as a result of the influence of other dialects.

- Loss of the indefinite /n/ suffix (tanwiin) on nouns.

- When this marker still appears, it is variously /an/, /in/, or /en/.

- In some Bedouin dialects it still marks indefiniteness on any noun, although this is optional and often used only in oral poetry.

- In other dialects it marks indefiniteness on post-modified nouns (by adjectives or relative clauses).

- All Arabic dialects preserve a form of the CA adverbial accusative /an/ suffix, which was originally a tanwiin marker.

- Loss of verb form IV, the causative.

- Verb form II sometimes gives causatives, but it is not productive.

- Uniform use of /i/ in imperfect verbal prefixes.

- CA had /u/ before form II, III and IV active, and before all passives, and /a/ elsewhere.

- Some Bedouin dialects in the Arabian peninsula have uniform /a/.

- Najdi Arabic has /a/ when the following vowel is /i/, and /i/ when the following vowel is /a/.

All sedentary dialects share the following additional innovations:

- Loss of a separately distinguished feminine plural in verbs, pronouns and demonstratives. This is usually lost in adjectives as well.

- Development of a new indicative-subjunctive distinction.

- The indicative is marked by a prefix, while the subjunctive lacks this.

- The prefix is /b/ or /bi/ in Egyptian Arabic and Levantine Arabic, but /ka/ or /ta/ in Moroccan Arabic. It is not infrequent to encounter /ħa/ as an indicative prefix in some Persian Gulf states; and, in South Arabian Arabic (viz. Yemen), /ʕa/ is used in the north around the San'aa region, and /ʃa/ is used in the southwest region of Ta'iz.

- Tunisian Arabic lacks an indicative prefix, and therefore does not have this distinction, along with Maltese and at least some varieties of Algerian and Libyan Arabic.

- Loss of /h/ in the third-person masculine enclitic pronoun, when attached to a word ending in a consonant.

- The form is usually /u/ or /o/ in sedentary dialects, but /ah/ or /ih/ in Bedouin dialects.

- After a vowel, the bare form /h/ is used, but in many sedentary dialects the /h/ is lost here as well. In Egyptian Arabic, for example, this pronoun is marked in this case only by lengthening of the final vowel and concomitant stress shift onto it, but the "h" reappears when followed by another suffix.

- ramā "he threw it"

- maramahūʃ "he didn't throw it"

The following innovations are characteristic of many or most sedentary dialects:

- Agreement (verbal, adjectival) with inanimate plurals is plural, rather than feminine singular, as in CA.

- Development of a circumfix negative marker on the verb, involving a prefix /ma-/ and a suffix /-ʃ/.

- In combination with the fusion of the indirect object and the development of new mood markers, this results in verbal complexes that are approaching polysynthetic languages in their complexity.

- An example from Egyptian Arabic is

- /ma-bi-t-ɡib-u-ha-lnaː-ʃ/

- [negation]-[indicative]-[2nd.person.subject]-bring-[plural.subject]-her-to.us-[negation]

- "You (plural) aren't bringing her to us."

- (NOTE: Versteegh glosses /bi/ as continuous.)

- In Egyptian, Tunisian and Moroccan Arabic, the distinction between active and passive participles has disappeared except in form I and in some Classical borrowings.

- These dialects tend to use form V and VI active participles as the passive participles of forms II and III.

Phonetics

- CA /ʔ/ is lost except initially.

- Depending on the exact phonetic environment, this either caused reduction of two vowels into a single long vowel or diphthong (when between two vowels), insertion of a homorganic glide /j/ or /w/ (when between two vowels, the first of which was short or long /i/ or /u/ and the second not the same), lengthening of a preceding short vowel (between a short vowel and a following non-vowel), or simple deletion (elsewhere). This resulted initially in a large number of complicated morphophonemic variations in verb paradigms.

- In CA and Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), /ʔ/ is still pronounced.

- However, because this change had already happened in Meccan Arabic at the time the Qur'an was written, it is reflected in the orthography of written Arabic, where a diacritic known as hamza is inserted either above an alif, waaw or yaa, or "on the line" (between characters); or in certain cases, a diacritic alif madda ("lengthened alif") is inserted over an alif. (As a result, proper spelling of words involving /ʔ/ is probably the most difficult issues in Arabic orthography. Furthermore, actual usage is inconsistent in many circumstances.)

- Modern dialects have smoothed out the morphophonemic variations, typically by deleting the associated verbs or moving them into another paradigm (for example, /qaraʔ/ "read" becomes /qara/, a third-weak verb).

- /ʔ/ has reappeared medially in various words due to borrowing from CA. (In addition, /q/ has become /ʔ/ in many dialects, although the two are marginally distinguishable in Egyptian Arabic, since words beginning with original /ʔ/ can elide this sound, whereas words beginning with original /q/ cannot.)

- ق qaaf (CA /q/) changes widely from variety to variety. In Bedouin dialects from Mauritania to Saudi Arabia, it is pronounced /ɡ/, as in most of Iraq. In the Levant and Egypt (except in Upper Egypt (the Sa'id) where it is influenced by that of Arabia), as well as Malta and some North African towns such as Tlemcen, it is pronounced as a glottal stop /ʔ/, apart from rural areas in the South West Levant where it becomes emphatic /kˤ/. In the Persian Gulf, it becomes /d͡ʒ/ in many words (adjacent to an original /i/), and is /ɡ/ otherwise. Elsewhere, it is usually realized as uvular /q/.

- ج jiim (CA /d͡ʒ/) too varies widely. In some Arabian Bedouin dialects, and parts of the Sudan, it is still realized as the medieval Persian linguist Sibawayh described it, as a palatalized /ɡʲ/. In Egypt and Yemen, it is a plain /ɡ/. In most of North Africa and the Levant, it is /ʒ/, apart from Algeria. In the Persian Gulf and Iraq, it often becomes /j/. Elsewhere, it is usually /d͡ʒ/.

- ك kaaf (CA /k/) often becomes /t͡ʃ/ in the Persian Gulf, Iraq, some Rural Palestinian dialects and in some Bedouin dialects (adjacent to an original /i/, particularly in the second singular feminine enclitic pronoun, where /t͡ʃ/ replaces an original /ik/ or /ki/). In a very few Moroccan varieties, it affricates to /kʃ/. Elsewhere, it remains /k/.

- ر raa (CA /r/) is pronounced like French /ʁ/ in a few areas: Mosul, for instance, and the Jewish variety in Algiers. In much of the Maghreb, a phonemic distinction has emerged between plain and emphatic r, thanks to the merging of short vowels.

- ث thaa, ذ dhaal (CA /θ/, /ð/) become /s, z/ in the Levant, and become /t, d/ in much of Egypt and North Africa (including Malta), but remain /θ/ and /ð/ in Tunisian, rural Palestinian, Eastern Libyan, and some rural Algerian dialects. In one Arabic-speaking town in Turkey, they become /f, v/.

- ت taa (CA /t/) (but not emphatic ط Taa (CA /tˤ/)) is affricated to /tˢ/ in Moroccan Arabic; this is still distinguishable from the sequence /ts/.

- ع ayin (CA /ʕ/) is pronounced in Iraqi Arabic and Kuwaiti Arabic with glottal closure: [ʔˁ]. In some varieties /ʕ/ is devoiced to [ħ] before /h/, for example in Cairene Arabic /bitaʕha/ → [bitaħħa] "hers". The residue of this rule applies also in the Maltese language, where neither etymological /h/ nor /ʕ/ are pronounced as such, but give [ħ] in this context: tagħha [taħħa] "hers".

- The nature of "emphasis" differs somewhat from variety to variety. It is usually described as a concomitant pharyngealization, but in most sedentary varieties it is actually velarization, or a combination of the two. (The phonetic effects of the two are only minimally different from each other.) Usually there is some associated lip rounding; in addition, the stop consonants /t/ and /d/ are dental and lightly aspirated when non-emphatic, but alveolar and completely unaspirated when emphatic.

- CA short vowels /a/, /i/ and /u/ suffer various changes.

- Original final short vowels are mostly deleted.

- Many Levantine Arabic dialects merge /i/ and /u/ into a phonemic /ə/ except when directly followed by a single consonant; this sound may appear allophonically as /i/ or /u/ in certain phonetic environments.

- Maghreb dialects merge /a/ and /i/ into /ə/, which is deleted when unstressed. Tunisian maintains this distinction, but deletes these vowels in non-final open syllables.

- Moroccan Arabic, under the strong influence of Berber, goes even further. Short /u/ is converted to labialization of an adjacent velar, or is merged with /ə/. This schwa then deletes everywhere except in certain words ending /-CCəC/.

- The result is that there is no more distinction between short and long vowels; borrowings from CA have "long" vowels (now pronounced half-long) uniformly substituted for original short and long vowels.

- This also results in consonant clusters of great length, which are (more or less) syllabified according to a sonority hierarchy. (For some subdialects, in practice, it is very difficult to tell where, if anywhere, there are syllabic peaks in long consonant clusters in a phrase such as /xsˤsˤk tktbi/ "you (fem.) must write". Other dialects, in the North, make a clear distinction; they say /xəssək təktəb/ "you want to write", but */xəssk ətkətb/ just won't do).

- In Egyptian Arabic and Levantine Arabic, short /i/ and /u/ (and merged /ə/, when it exists) are elided in various circumstances in unstressed syllables (typically, in open syllables; for example, in Egyptian Arabic, this occurs only in the middle vowel of a VCVCV sequence, ignoring word boundaries). In these dialects, however, clusters of three consonants are almost never permitted (absolutely never, in Egyptian Arabic). If such a cluster would occur, it is broken up through the insertion of i /ə/ – between the second and third consonants in Egyptian Arabic, and between the first and second in Levantine Arabic.

- CA long vowels are shortened in some circumstances.

- Original final long vowels are shortened in all dialects.

- In Egyptian Arabic and Levantine Arabic, unstressed long vowels are shortened.

- Egyptian Arabic also cannot tolerate long vowels followed by two consonants, and shorten them. (Such an occurrence was rare in CA, but often occurs in modern dialects as a result of elision of a short vowel.)

- In most dialects, particularly sedentary ones, CA /a/ and /aː/ have two strongly divergent allophones, depending on the phonetic context.

- Adjacent to an emphatic consonant and to /q/ (but not usually to other sounds derived from this, such as /ɡ/ or /ʔ/), a back variant [ɑ] occurs; elsewhere, a strongly fronted variant [æ] is used.

- There is a tendency for emphatic consonants to cause non-adjacent low vowels to be backed, as well; this is known as emphasis spreading. The domain of emphasis spreading is potentially unbounded; in Egyptian Arabic, the entire word is usually affected, although in Levantine Arabic and some other varieties, it is blocked by an /i/ or /j/ (and sometimes /ʃ/).

- The two allophones are in the process of splitting phonemically in some dialects, as [ɑ] occurs in some words (particularly foreign borrowings) even in the absence of any emphatic consonants anywhere in the word. (Some linguists have postulated additional emphatic phonemes in an attempt to handle these circumstances; in the extreme case, this requires assuming that every phoneme occurs doubled, in emphatic and non-emphatic varieties. Some have attempted to make the vowel allophones autonomous and eliminate the emphatic consonants as phonemes. Others have asserted that emphasis is actually a property of syllables or whole words rather than of individual vowels or consonants. None of these proposals seems particularly tenable, however, given the variable and unpredictable nature of emphasis spreading.)

- CA /r/ is also in the process of splitting into emphatic and non-emphatic varieties, with the former causing emphasis spreading, just like other emphatic consonants. Originally, non-emphatic [r] occurred before /i/ or between /i/ and a following consonant, while emphatic [rˤ] occurred elsewhere.

- To a large extent, Eastern Arabic dialects reflect this, while the situation is rather more complicated in Egyptian Arabic. (The allophonic distribution still exists to a large extent, although not in any predictable fashion; nor is one or the other variety used consistently in different words derived from the same root. Furthermore, although derivational suffixes (in particular, relational /-i/ and /-ijja/) affect a preceding /r/ in the expected fashion, inflectional suffixes do not.)

- In Moroccan Arabic, short /a/ and /i/ have merged, obscuring the original distribution. In this dialect, the two varieties have completely split into separate phonemes, with one or the other used consistently across all words derived from a particular root except in a few situations.

- In Moroccan Arabic, the allophonic effect of emphatic consonants is more pronounced than elsewhere.

- Full /a/ is affected as above, but /i/ and /u/ are also affected, and are lowered to [e] and [o], respectively.

- In some varieties, such as in Marrakesh, the effects are even more extreme (and complex), where both high-mid and low-mid allophones exist ([e] and [ɛ], [o] and [ɔ]), in addition to front-rounded allophones of original /u/ ([y], [ø], [œ]), all depending on adjacent phonemes.

- On the other hand, emphasis spreading in Moroccan Arabic is less pronounced than elsewhere; usually it only spreads to the nearest full vowel on either side, although with some additional complications.

- Emphasis spreading also pharyngealizes consonants between the source consonant and affected vowels, although the effects are much less noticeable than for vowels, since the rise of emphasis spreading is associated with a concomitant decrease in the amount of pharyngealization of emphatic consonants.

- Interestingly, emphasis spreading does not affect the affrication of non-emphatic /t/ in Moroccan Arabic, with the result that these two phonemes are always distinguishable regardless of the nearly presence of other emphatic phonemes.

- Certain other consonants, depending on the dialect, also cause backing of adjacent sounds, although the effect is typically weaker than full emphasis spreading and usually has no effect on more distant vowels.

- The uvular consonants /x/ and /q/ often cause partial backing of adjacent /a/ (and lowering of /u/ and /i/ in Moroccan Arabic). For Egyptian Arabic and Moroccan Arabic, the effect is sometimes described as half as powerful as an emphatic consonant, as a vowel with uvular consonants on both sides is affected similarly to having an emphatic consonant on one side.

- Interestingly, the pharyngeal consonants /ħ/ and /ʕ/ cause no emphasis spreading and may have little or no effect on adjacent vowels. In Egyptian Arabic, for example, an /a/ adjacent to either sound is a fully front [æ]. In other dialects, /ʕ/ is more likely to have an effect than /ħ/.

- In some Gulf Arabic dialects, /w/ and/or /l/ causes backing.

- In all dialects, the word الله /alˤlˤāh/ Allāh has backed [ɑ]'s and strongly pharyngealized /l/.

- CA diphthongs /aj/ and /aw/ have become /eː/ and /oː/ (but merge with original /iː/ and /uː/ in Maghreb dialects, which is probably a secondary development). The diphthongs are maintained in the Maltese language and some urban Tunisian dialects, particularly that of Sfax, while /eː/ and /oː/ also occur in some other Tunisian dialects, such as Monastir.

- The placement of the stress accent is extremely variable between varieties; nowhere is it phonemic.

- Most commonly, it falls on the last syllable containing a long vowel, or a short vowel followed by two consonants; but never farther from the end than the third-to-last syllable. This maintains the presumed stress pattern in CA (although there is some disagreement over whether stress could move farther back than the third-to-last syllable), and is also used in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA).

- In CA and MSA, stress cannot occur on a final long vowel; however, this does not result in different stress patterns on any words, because CA final long vowels are shortened in all modern dialects, and any current final long vowels are secondary developments from words containing a long vowel followed by a consonant.

- In Egyptian Arabic, the rule is similar, but stress falls on the second-to-last syllable in words of the form ...VCCVCV, as in /makˈtaba/.

- In Maghrebi Arabic, stress is final in words of the (original) form CaCaC, after which the first /a/ is elided. Hence جَبَل "mountain" (MSA /ˈd͡ʒabal/) becomes /ˈʒbəl/.

- In Moroccan Arabic, phonetic stress is often not recognizable.

- Most commonly, it falls on the last syllable containing a long vowel, or a short vowel followed by two consonants; but never farther from the end than the third-to-last syllable. This maintains the presumed stress pattern in CA (although there is some disagreement over whether stress could move farther back than the third-to-last syllable), and is also used in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA).

See also

- Arabic diglossia

- Arabic (disambiguation).

Further reading

- Durand, O., (1995), Introduzione ai dialetti arabi, Centro Studi Camito-Semitici, Milan.

- Fischer W. & Jastrow O., (1980) Handbuch der Arabischen Dialekte, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden.

- Heath, Jeffrey "Ablaut and Ambiguity: Phonology of a Moroccan Arabic Dialect" (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987)

- Holes, Clive (2004) Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1-58901-022-1

- Versteegh, Dialects of Arabic

- Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997)

- George Grigore, (2007). L'arabe parlé à Mardin. Monographie d'un parler arabe périphérique. Bucharest: Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti, ISBN (13) 978-973-737-249-9 [1]

- Columbia Arabic Dialect Modeling (CADIM) Group

- Israeli Hebrew and Modern Arabic – a Few Differences and Many Parallels

References

- ↑ http://www.arabacademy.com/faq/arabic_language Questions from Prospective Students on the varieties of Arabic Language - online Arab Academy

- ↑ Stolz, T. (2003) Not quite the right mixture: Chamorro and Malti as candidates for the status of mixed language, in Y. Matras/P. Bakker (eds.) The mixed languages debate. Theoretical and empirical advances. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 271-315. P. 273

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||